Nat Turner

the person, the literature, and the legacy

To start with some self-pity: Everyone’s reading year end reviews always make me feel a tad crummy. Even though I am a regular reader I am always far short of my TBR (“to be read”) list(s) (both the TBR of things I purely want to read and the TBR of things I feel obligated to read/would probably still enjoy). Impressive lists, photos of tidy stacks of books, and catchy personalized infographics will sometimes prompt some of my more self-conscious thoughts: Do I scroll too much? Sleep too much? Do I blame the kids? What does it mean that I both don’t meet my reading goals or anything near a set of exercising goals? Maybe my TBR is unrealistic to start with, but just look at everyone else’s Goodreads years in review!

Now that that is out of the way, there is a book I read this year that has gotten under my skin. The novel The Confessions of Nat Turner by William Styron is a fictionalized account of the non-fictional Nat Turner. It was one of the worst books I read all year (maybe tied for the one I talk about in this post). As usual for books I don’t enjoy, I got it at a used book sale and opened it to gain a broader understanding of regional history. All I had known previously was that Nat Turner was a famous leader of a slave rebellion, and that he had some kind of religious (Christian) motivation for his massacre. As it turns out, I was going to learn very little about the actual Turner from Styron’s lengthy, salacious, and for lack of a better word – sus – version of historical fiction.

After I slogged through the book, I was shocked to learn more about its origins: The man got a $250,000 advance for his book in the 1960s (which would literally be about $2.5 million in today’s dollars). Styron is also the author of the infamous Sophie’s Choice, and Confessions of Nat Turner actually won the Pulitzer Prize in 1967. Also, perhaps unsurprisingly, the book took significant departures from the actual historic text of the same name, and from some of the scant evidence gathered from newspaper articles printed in the wake of his uprising/massacre.

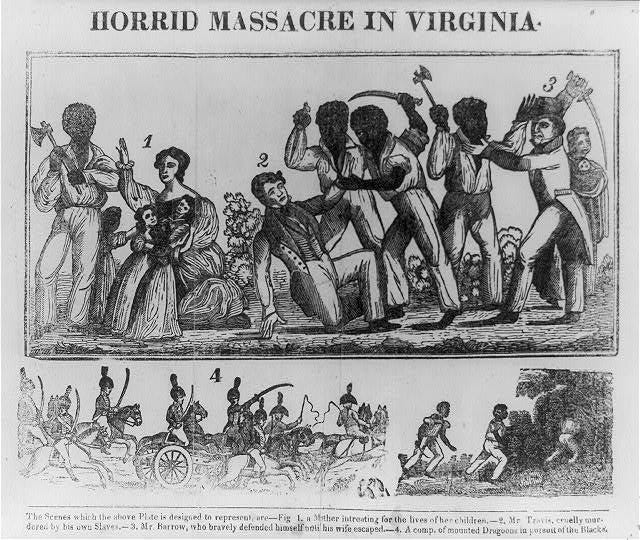

Here are some of the historical details of Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831 South Carolina (most of this is coming from Wikipedia, for better or for worse, but there is lots of scholarship on Nat Turner, the rebellion, and the aftermath). Nat Turner rallied up to 70 enslaved and free black men who killed between 55 and 85 white people in cold blood with knives, farming equipment, and other items turned into weapons (Turner himself only murdered one individual, whom he killed with a fence post). The rebels moved from house to house and freed the property’s slaves, seized weapons, and killed their inhabitants, including women and children. After two days the rebellion was quelled by militia, and after several weeks Turner was found, arrested, and executed. Thomas Gray published the pamphlet “The Confessions of Nat Turner” based on interviews with Turner during his time in jail. Waves of retaliatory violence against blacks completely unrelated to the massacre followed, and southern state governments took legal means to double down against their enslaved populations. Legislatures enacted anti-literacy laws forbidding reading and writing for enslaved and free blacks, and religious meetings required a white minister in attendance.

Despite the acclaim and the literal Pulitzer lavished on this book, it also met stiff criticism and continues to stoke debate. Some of this stemmed from the glaring differences between the historical and Styron Nat Turner. For instance, the actual Turner had a wife, but Styron writes her out of the story and instead depicts Turner burning with lust for the white women in his midst. Furthermore, Styron’s Turner was filled with remorse and doubt as he approached his execution, whereas his interviewer Thomas Gray noted that Turner was “an exceptional figure, distinguished from his followers by his honesty, his commanding intelligence, and his firm belief in the righteousness.” Soon after the book was released, the book William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond collected critical essays. Together these writers argued that Styron didn’t just create a white revisionist past for Nat Turner; he undermined the contemporary civil rights movement and emerging Black Power movement. I read a few essays from Ten Black Writers Respond and the consensus seemed to be that “Styron-Turner” reinforced racist stereotypes of black men’s sexual threats to white women and of black dependence on whites for survival or direction. The authors were also (arguably to the point of outright sexism) particularly incensed by how emasculated Styron-Turner was. Debate over Styron’s book continues, such as in this piece by a literary scholar and fiction writer, and this retrospective piece by Styron’s own daughter, who is also an author (and I hate that the article is behind a paywall, especially since I’m pretty sure I somehow read this article back in June when I finished Styron’s book).

Aside from Styron’s book, I encountered Nat Turner a few other times in books I read in 2025. These books, along with Styron’s, has had me wondering what kind of impact brutal massacres – though Turner’s in particular – and their legacies leave on their societies. Mark Noll’s 2008 book, God and Race in American Politics: A Short History, examines the impact of religion in American life “from Nat Turner to George W. Bush” – identifying Turner’s rebellion to the status of a national turning point. Others elevated Nat Turner as having released a positive, liberatory current. Angela Davis in her 1974 autobiography recalls her all black Birmingham school where students were not only taught the official school board curriculum but also “a strong positive identification with our people and our history.” “As we learned about George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln, we also became acquainted with Black historical figures. Granted, the Board of Education would not permit the teachers to reveal to us the exploits of Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey. But we were introduced to Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman” (Denmark Vesey was the orchestrator of a thwarted slave revolt in 1822, and he was, like Turner, an active and professing Christian).

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2015 book Between the World and Me also made a passing reference to Turner as an exemplar of the kind of political consciousness to which he aspired.

“Every February my classmates and I were herded into assemblies for a ritual review of the Civil Rights Movement. Our teachers urged us toward the example of freedom marchers, Freedom Riders, and Freedom Summers, and it seemed that the month could not pass without a series of films dedicated to the glories of being beaten on camera….Why are they showing this to us? Why were only our heroes nonviolent? I speak not of the morality of nonviolence, but of the sense that blacks are in especial need of this morality.”

In a section explaining why Malcom X and his explicit disavowal of nonviolence was liberatory for him, Coats reflected that when hearing Malcolm X, he thought: “Perhaps I too might live free. Perhaps I too might wield the old power that animated the ancestors, that lived in Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, [and others] and speak – no, act — as though my body were my own.”

I have already admitted here that I’m a bit of a latecomer to American history, and I’m curious if readers of this blog were aware of Nat Turner, or even Styron’s novel about him. I have a lot of ambivalence while learning about his legacy, and also have a lot of ambivalence trying to write about it here. But what does it mean that Turner’s rebellion came after two hundred years of a population living under a system in which people could not control their own bodies, had no political representation whatsoever, could not even keep their own families together, and experienced all of this under the threat and execution of more violence? What does it mean that a massacre so violent was met with yet more acute and indiscriminate violence? And that this violence ultimately didn’t end up succeeding in its mission of preserving the system of slavery? What does it mean that something so violent can and does live on as a national turning point, and/or as a symbol for political consciousness? And how do societies that have historically relied on major imbalances of power go about grappling with events and figures that emerged in this imbalance?